21 Oct 2025 European Bird Hunting Developments: Teal, Shoveler, and Pintail

Alongside last month’s article on the three species recommended for Adaptive Harvest Management by the European Commission, three other duck species were identified as being at risk of unsustainable hunting: the Eurasian Teal, the Northern Pintail, and the Northern Shoveler. In this article, which is slightly longer than usual and includes scientific references, we dive into the details.

Firstly, we want to highlight issues concerning the data used for these assessments. For instance, the use of harvest estimates that are higher than the population estimates, which led to hunting being deemed unsustainable, in sharp contrast with the increasing flyway populations of these species.

This is most likely caused by underestimating population sizes, which is a common issue in bird monitoring (Nagy et al., 2022). Taking the Teal as an example, as a very widespread species, it uses virtually all types of wetlands available. The Shoveler also has general habitat requirements and breeds in most wetland types (Mitchell, 2005). However, common monitoring schemes only focus on key waterbird sites. This might significantly underestimate the population sizes of such species. Support for this comes, for example, from Mendez et al. (2015), who found that the UK estimates for these species could be significantly underestimated by the current monitoring scheme (WeBS) using a stratification-based approach, which considers the environmental needs of each species (unlike traditional schemes). This new approach resulted in national population estimates exceeding the published figures by more than 50% for the Teal, and by approximately 35% and 45% for the Pintail and Shoveler, respectively. These authors recommend adopting this method in future estimates.

However, while the estimates of population size are likely underestimated, the population trends are of good quality and should serve as the reference for evaluating the sustainability of hunting.

Therefore, the key question is: what are the population trends of these species?

Teal (Anas crecca)

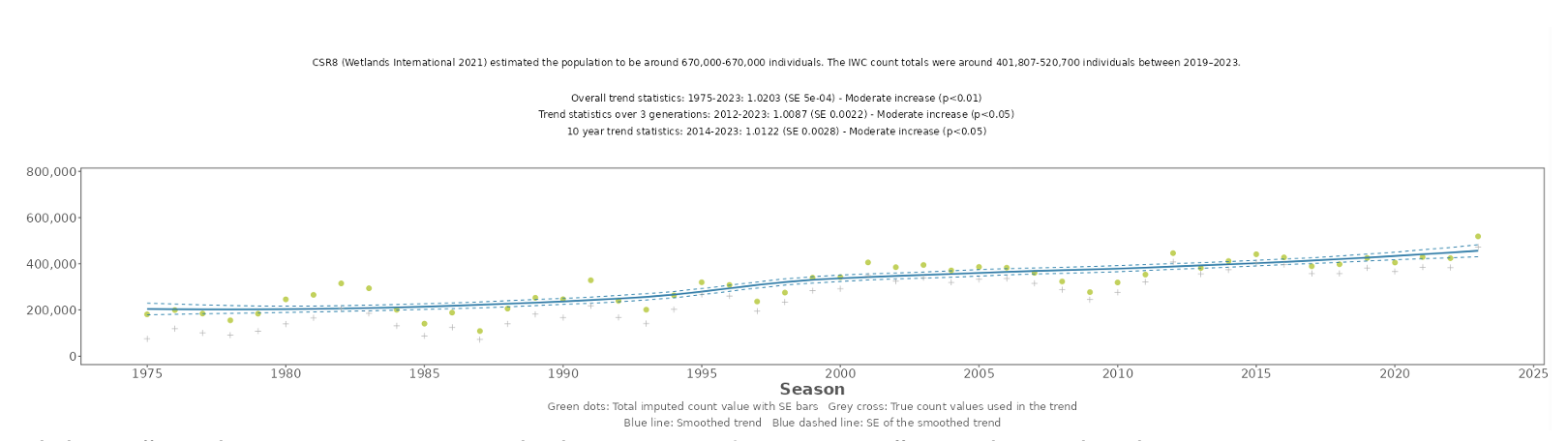

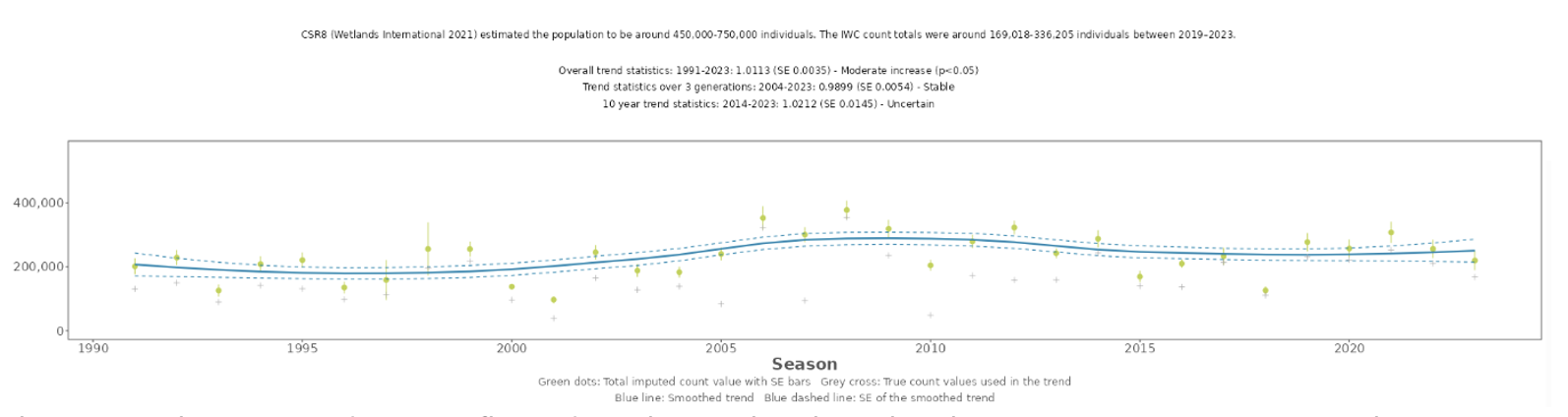

The Teal’s “North-west Europe” population has been steadily increasing over the past 50 years.

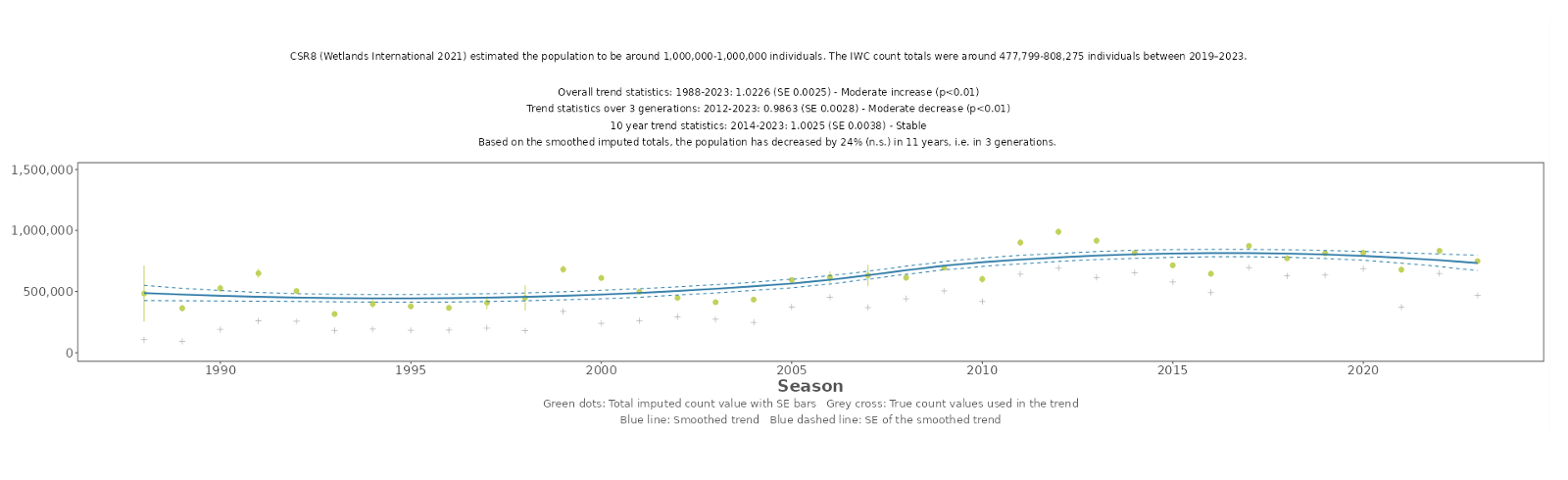

While its “W Siberia & NE Europe–Black Sea & Mediterranean” population has been increasing over the long term, it has now stabilised in the last decade.

While its “W Siberia & NE Europe–Black Sea & Mediterranean” population has been increasing over the long term, it has now stabilised in the last decade.

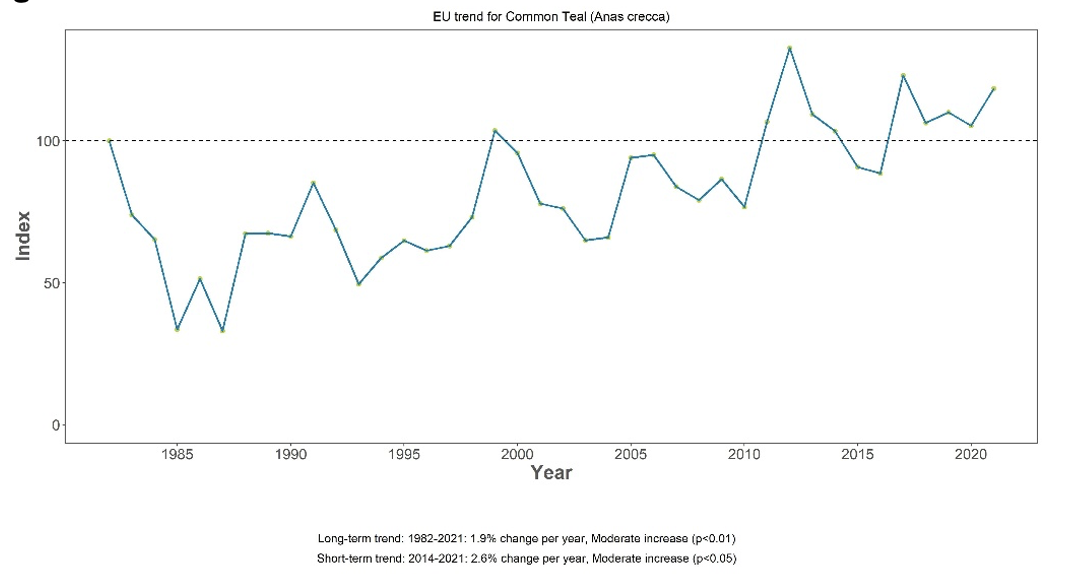

These population trends are reflected at EU level, where the Teal’s population has also been steadily rising.

These population trends are reflected at EU level, where the Teal’s population has also been steadily rising.

Pintail (Anas acuta)

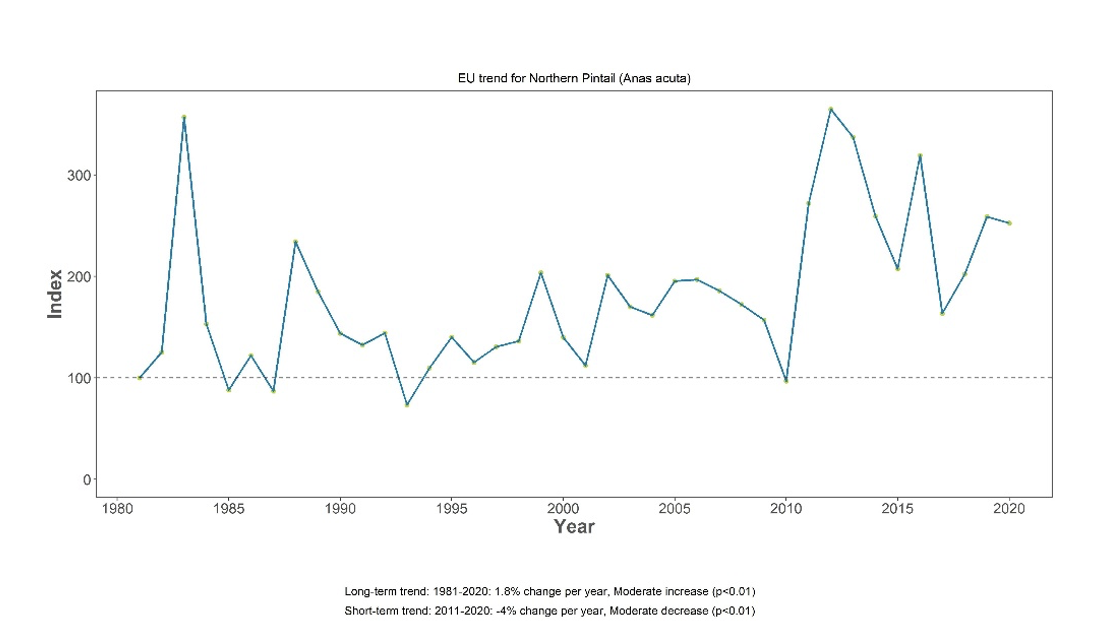

Similarly, the Pintail’s “North-west Europe” population has also shown a long-term increase.

While it’s “W Siberia, NE & E Europe-S Europe & West Africa”, the population has been increasing over the long term but has now stabilised.

While it’s “W Siberia, NE & E Europe-S Europe & West Africa”, the population has been increasing over the long term but has now stabilised.

These population trends are reflected at the EU level, with a long-term increase in Pintail wintering numbers.

These population trends are reflected at the EU level, with a long-term increase in Pintail wintering numbers.

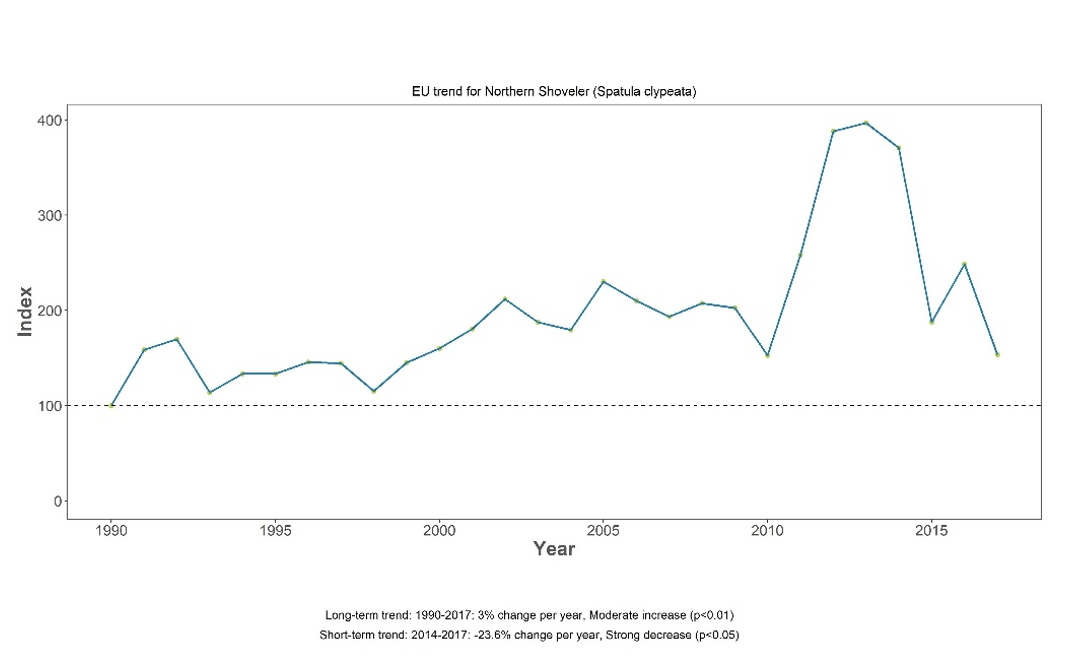

Shoveler (Spatula clypeata)

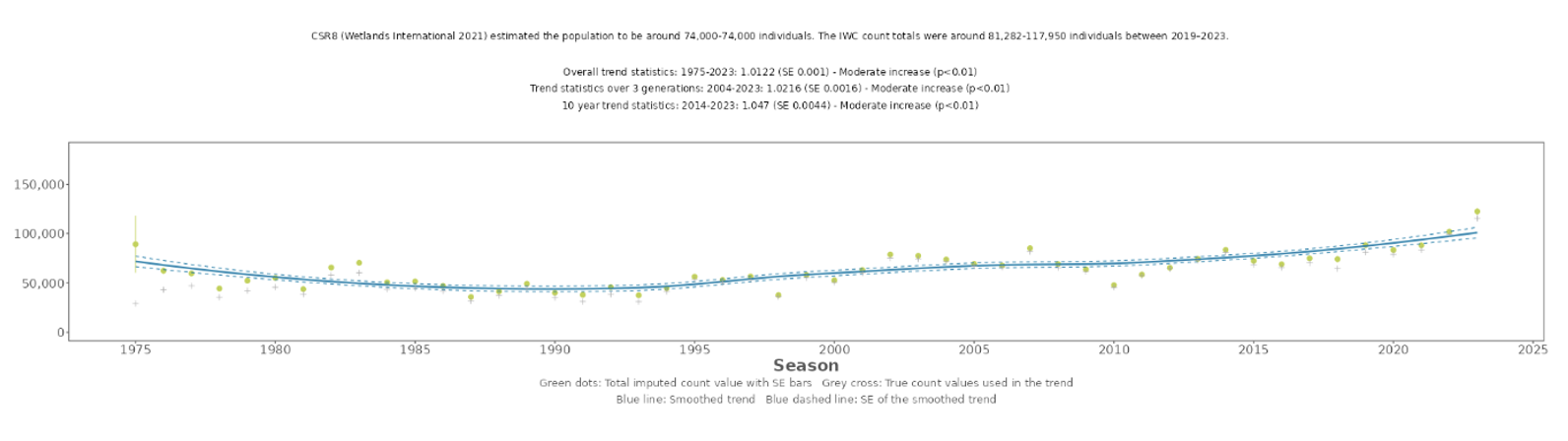

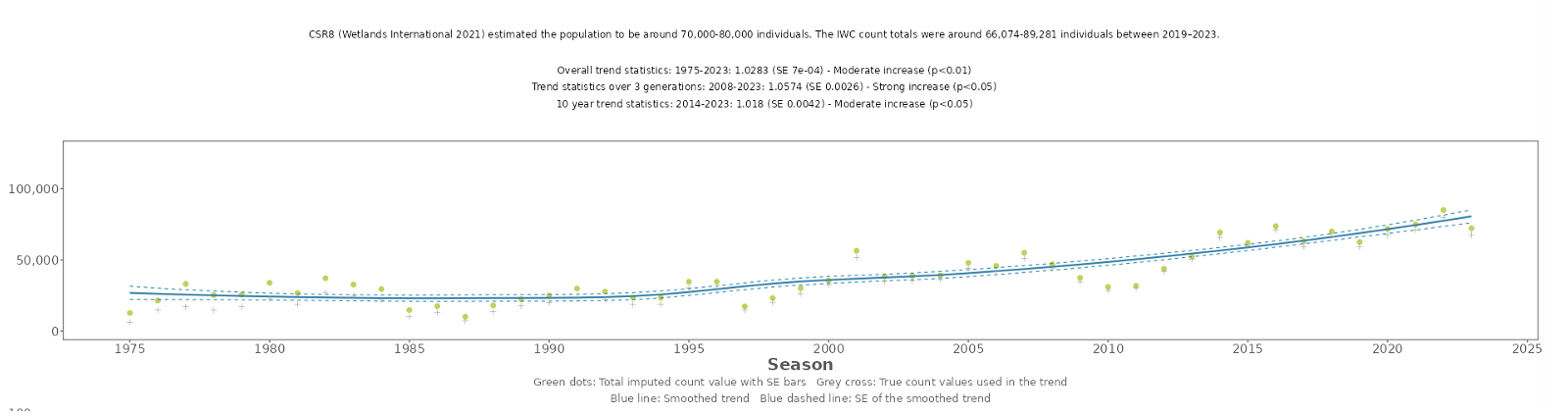

The Shoveler’s “North-west & Central Europe” population has also been steadily increasing over the past 50 years, even noting a strong increase.

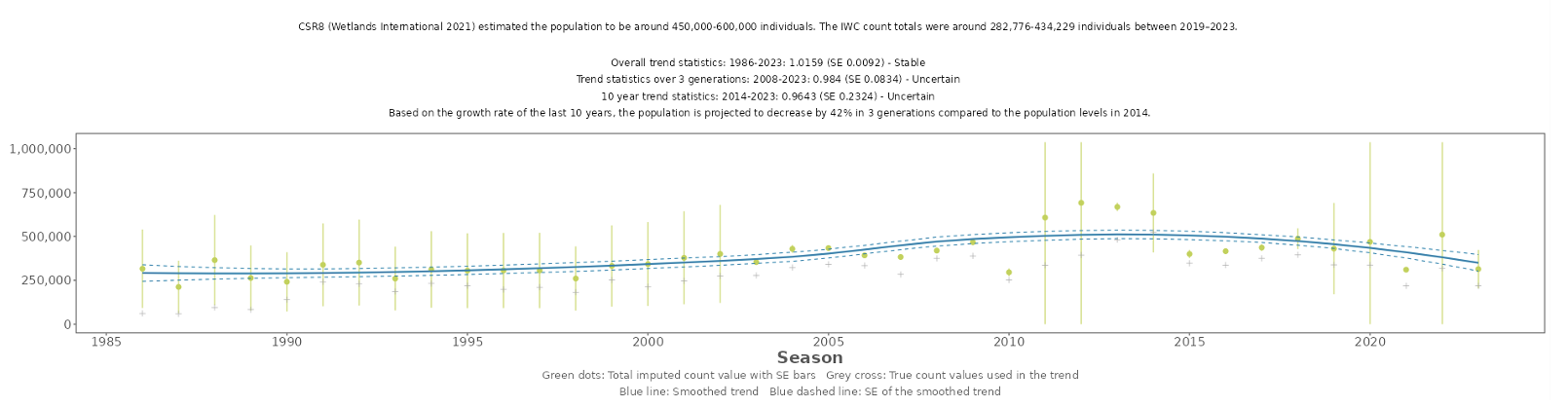

While it’s “W Siberia, NE & E Europe-S Europe & West Africa” population has been stable over the last 40 years, the data is of lesser quality.

While it’s “W Siberia, NE & E Europe-S Europe & West Africa” population has been stable over the last 40 years, the data is of lesser quality.

These population trends are reflected at EU level, with increasing wintering trend over the long-term.

These population trends are reflected at EU level, with increasing wintering trend over the long-term.

All these trends suggest that these species are now more numerous than they were decades ago, when the Birds Directive was introduced, at both population (“flyway”) and EU wintering levels. Importantly, the counts supporting these trends are conducted in late winter, mainly after hunting has taken place.

Since hunting takes place in winter, these population trends should be used to assess hunting sustainability and to verify the results of the rapid assessment. Such an appraoch is recommended by the authors of the statistical tool utilised for the assessment, who specify that “while popharvest provides a useful platform for rapid assessments of sustainability, it cannot substitute for sufficient expertise and experience in harvest theory and management” (Johnson et al., 2024). The increasing flyway and EU wintering populations indicate that hunting is sustainable.

These species’ populations are increasing, so why are they labelled as “unsecure” or “declining”?

While these species have increasing flyway populations, and in the EU, increasing wintering trends, they were included in the list of “species in unsecure EU status” because they have decreasing breeding trends in the EU. The decreasing breeding populations of ducks in the EU are a serious concern. However, this issue is not related to hunting harvests but to the significant loss of quality habitats they rely on.

For example, the Teal is a typical short-lived and prolific species, indicating that productivity, rather than survival, is the primary driver of population dynamics. Productivity is unaffected by hunting but is influenced by factors such as loss of breeding habitats or predation. Similarly, habitat quality and availability are the main factors determining the Shoveler’s breeding success, so actions aimed at restoring habitat are expected to be most effective for the Shoveler (Keller et al., 2020). While the Pintail’s EU breeding range is almost entirely confined to Finland and Sweden, efforts to reduce habitat loss and nest predation have been identified as priorities (Keller et al., 2020). Therefore, improving breeding conditions remains the most important priority for these species.

It is important to emphasise that the EU holds relatively limited significance for these species’ breeding populations, as it accounts for only a small part of their breeding range. Most of the European breeding population of Teal breeds in Russia, with only about 30% breeding within the EU (Powolny & Czajkowski, 2022). Likewise, the majority of the European breeding populations of Pintail and Shoveler are found in Russia (Keller et al., 2020; Czajkowski et al., 2022).

It is also important to recognise that, although these species are hunted—often in very low numbers in most parts of Europe—they encourage waterfowl hunters to invest significantly in habitat management. In this context, the emphasis should be on expanding and replicating habitat conservation efforts rather than on restricting hunters’ motivation to invest in such work, which would lead to no positive outcomes for the populations.

FACE’s Biodiversity Manifesto shows that 40% of hunters’ habitat conservation initiatives focus on wetlands, and that 36% of all projects address the conservation of birds and their habitats. For example, in Italy, investments amounting to hundreds of thousands of euros have been carried out for more than 20 years to conserve wetlands in the Po Delta, ensuring a quality wintering area at no cost to the community. Similarly, in Ireland, 170 Irish game hunting clubs are involved in wetland management for ducks. Several national hunting organisations also contribute to funding top-quality breeding habitats for waterfowl in northern Europe. All these projects involve private investment by the hunting community, either alongside public funding or entirely self-financed.

Conclusion

In conclusion, although the rapid assessment of hunting sustainability indicated that harvest of these species might potentially be unsustainable, ground-truthing of the results, as recommended by the statistical tool’s own authors, enables us to reasonably conclude that hunting in the EU is sustainable because both the EU wintering trends and the flyway populations are increasing. The priority should therefore be to restore quality breeding habitats to address the decline in breeding numbers in the EU, which is why these species were initially included in the list of species of unsecure EU status. As hunters are a key force in habitat management and restoration, unnecessarily restricting hunting could have detrimental effects on the EU’s habitats while bringing no conservation benefits.

Sources:

- CSR9 trends: https://iwc-wi.shinyapps.io/csr9/

- Czajkowski, A., Powolny, T. & Fox, A.D. (2022). Northern Shoveler Spatula clypeata. Pp. 161-174 in Powolny, T. & Czajkowski, A. (eds). Conservation and Management of Game Birds in Europe. Species of Annex II/A of the Birds Directive. OMPO Publication. Paris, France. p. 464.

- EU wintering trends: https://iwc.wetlands.org/index.php/eumsi

- Johnson, F. A., Eraud, C., Francesiaz, C., Zimmerman, G. S., & Koneff, M. D. (2024). Using the R package popharvest to assess the sustainability of offtake in birds. Ecology and Evolution, 14(4), e11059.

- Keller, V., Herrando, S., Voříšek, P., Franch, M., Kipson, M., Milanesi, P., Martí, D., Anton, M., Klvaňová, A., Kalyakin, M.V., Bauer, H.-G. & Foppen, R.P.B. (2020). European Breeding Bird Atlas 2: Distribution, Abundance and Change. European Bird Census Council & Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

- Méndez, V., Austin, G. E., Musgrove, A. J., Ross-Smith, V. H., Hearn, R. D., Stroud, D. A., … & Holt, C. A. (2015). Use of environmental stratification to derive non-breeding population estimates of dispersed waterbirds in Great Britain. Journal for Nature Conservation, 28, 56-66.

- Mitchell, C. (2005). Northern Shoveler Anas clypeata.

- Nagy, S., Langendoen, T., Frost, T. M., Jensen, G. H., Markones, N., Mooij, J. H., … & Suet, M. (2022). Towards improved population size estimates for wintering waterbirds. Ornithologische Beobachter, 119(4).

- Powolny, T., & Czajkowski, A. (2022). Conservation and management of game birds in Europe. Species of Annex II/A of the Birds Directive.